In early December 2025, Nestlé quietly began recalling batches of infant formula produced at its factory in Nunspeet, the Netherlands. Within weeks, what started as a single-market precautionary withdrawal had exploded into one of the largest food safety crises in the company’s history: a recall spanning more than 60 countries, affecting hundreds of product lines across multiple brands including SMA, Beba, Guigoz and Alfamino.

The culprit was cereulide, a heat-stable toxin produced by Bacillus cereus bacteria. It had been found in arachidonic acid-rich oil (known as ARA) a specialised fatty acid added to infant formula to support brain and retina development.

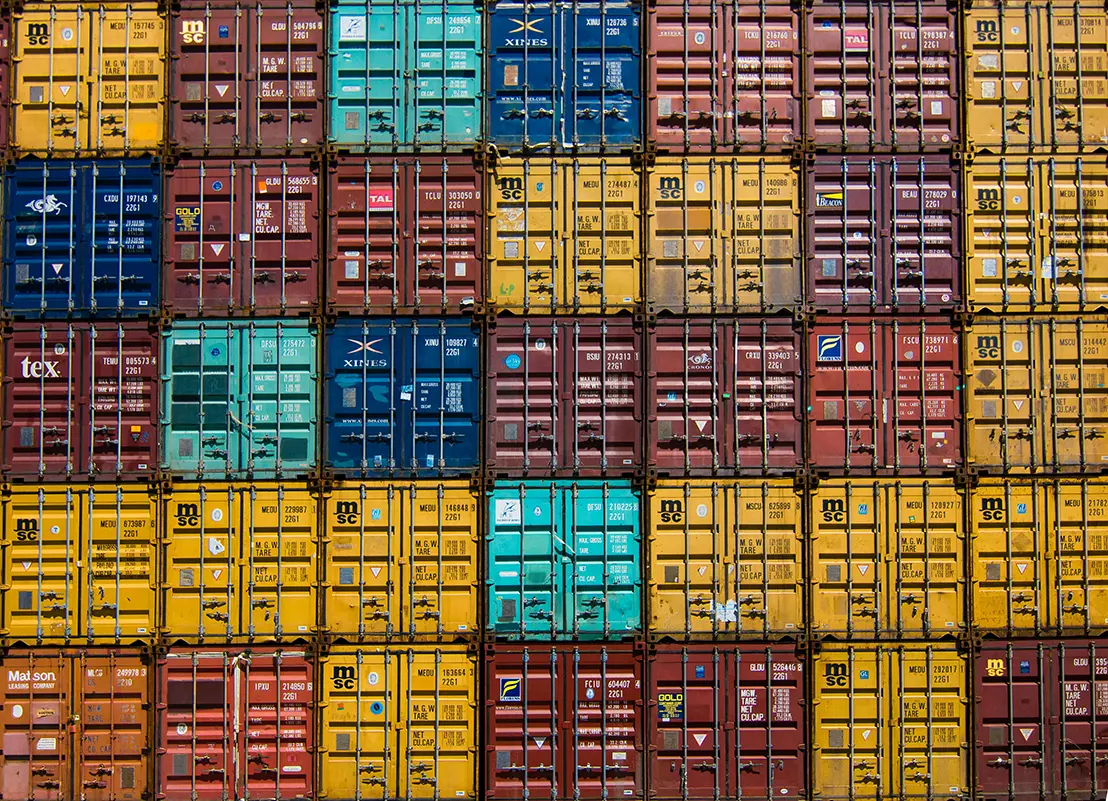

The contaminated ARA came from a single supplier in Wuhan, China, and had wormed its way into the production lines of not just Nestlé, but Danone, Lactalis and Swiss outfit Hochdorf as well. Between them, these companies supply infant formula to virtually every major consumer market on earth.

The fallout has been severe. French authorities are investigating the deaths of two babies reported to have consumed affected Nestlé formula. A Belgian infant was hospitalised with vomiting and diarrhoea. Singapore confirmed a likely cereulide case, and Brazil reported two sick babies.

Consumer rights groups, food safety charities, and parents across dozens of countries have torn into the industry. FoodWatch, the Netherlands-based watchdog, slammed Nestlé for what it called a “serious breakdown” in transparency.

But beyond the immediate health concerns, the ARA crisis raises fundamental questions for procurement professionals: how did a single Chinese supplier manage to bring the entire global infant formula industry to its knees? And, given this monumental disaster, should companies even be sourcing these critical nutritional ingredients from China?

Invisible Dependency

To answer that, you need to understand just how deeply China is embedded in the global food supply chain.

China isn’t just a major supplier of nutritional ingredients; it’s the dominant one, accounting for 70-80% of global production capacity for many essential vitamins and minerals.

And to be clear: for the most part, this system works. Chinese manufacturers have built incredibly safe, high-tech production lines that supply the bulk of the world’s nutritional additives without incident. If you’ve eaten anything processed today — breakfast cereal, fortified milk, even that vitamin supplement — there’s a very good chance you’ve got a piece of this supply chain sitting in your stomach right now!

As of 2024, China accounts for between 70 and 80% of global production capacity for ascorbic acid, the synthetic form of vitamin C. For the United States, the dependency is near-total: roughly 90% of the vitamin C consumed in the country is sourced from Chinese producers, almost all of it manufactured in a handful of dedicated chemical parks.

The concentration extends across the full spectrum of industrial nutrition. Chinese manufacturers supply an estimated 73% of global feed-grade vitamin A, 94% of vitamin B2, and the bulk of the essential amino acids used in commercial flavourings.

According to the American Feed Industry Association, the U.S. imports an average of 78% of its vitamins directly from China. For certain vitamins like biotin, that figure reaches 100%.

This dependency could become a political flashpoint. In December, a bipartisan crew of sixteen Congress members wrote to President Trump urging him to get domestic vitamin manufacturing sorted, calling the China dependency a straight-up national security threat.

In many ways, China’s dominance in nutritional ingredients mirrors the rare earth story. For decades, Beijing backed these industries with heavy subsidies, allowing Chinese manufacturers to undercut foreign competitors on price. Over time, foreign producers closed down, and China accumulated all the technical expertise. Now that know-how is extremely difficult (and expensive) for other countries to replicate.

Processing Dominance

Beyond chemistry, China also converts much of the raw biomass sourced worldwide into intermediate goods for re-export.

The tomato industry is a case in point. In 2024, China processed a record 11 million tonnes of fresh tomatoes into paste, consolidating its position as the world’s largest exporter. Virtually none of this output is consumed domestically. Instead, it is shipped in bulk drums to Italy, Africa and the Middle East, where it is reconstituted, repackaged and (here’s the kicker) sometimes sold as locally branded sauce.

A similar pattern holds in seafood. Around 75% of fish imported by China, including Russian Alaskan pollock and Norwegian cod, is processed and re-exported rather than consumed domestically. In tilapia alone, China commands roughly 30% of global supply.

In each case, the value China captures isn’t in the raw commodity but in the processing step — the conversion of bulk agricultural inputs into standardized, export-ready intermediates.

This concentration creates efficiency, but it also creates risk.

Four Risks Buyers Overlook

The ARA contamination crisis has exposed serious gaps in how some Western companies check ingredients from China. Quality testing is the obvious issue. But there are also specific risks when sourcing nutrition ingredients that procurement teams routinely underestimate:

Facility contamination risk gets routinely overlooked. Some Chinese manufacturers make nutritional supplements in the same facilities where they produce pharmaceuticals, pesticides or industrial chemicals. Not surprisingly, this dramatically raises the chance of contamination. Buyers need to be asking: “What else does this factory make?”

Safety certificates create false comfort. Standards like ISO 9001 or FDA approval are just snapshots in time. A certificate doesn’t tell you what happens at 3 a.m. when a factory manager accepts a questionable batch to hit a deadline. That’s why both good relationships and surprise inspections are essential.

Another big risk is depending on a single source. The entire infant formula industry sourced ARA from what appears to be just a handful of producers, with one company — Cabio Biotech in Wuhan — dominating the market. When that single supplier failed, the fallout spread across the entire industry.

The crisis also exposed a regulatory blind spot. Until contamination forced action, there was no EU safety limit for cereulide in infant formula. As one University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna researcher put it: “Nobody knows what this ‘low’ concentration actually means, because the limit has not been defined yet.”

European regulators are developing guidelines expected early this month, but safety rules are still catching up to global supply chains. Don’t assume regulatory approval means comprehensive risk coverage.

The Kinyu View

The infant formula crisis shouldn’t prompt companies to stop sourcing ingredients from China. That’s neither realistic nor particularly useful advice. These same risks (facility contamination, single-source dependency, regulatory gaps) exist regardless of where you source.

Plus, China’s position in the nutrition supply chain isn’t going anywhere. The infrastructure is already built, the technical expertise is concentrated there, and the economics still make sense for most buyers.

The real lesson for procurement teams is simpler: learn to source from China intelligently.

That means moving beyond compliance checkboxes. It means genuinely understanding your multi-tier supplier networks. Not just your direct vendor, but their suppliers too. It means maintaining geographic redundancy where you can afford it. And most importantly, it means building supplier relationships where a factory manager facing a quality decision at 3 a.m. picks up the phone to escalate the problem rather than quietly accepting a questionable batch to hit a deadline.